I'm realizing being a writer has little to do with publishing and a whole lot to do with putting words on the page. I'm a writer not because I'm published, but because I collect words in order to make sense of the world.

- Ruth Ayres Writing instruction is one of the most misunderstood disciplines in the field of education. Often, teachers trying to teach struggling writers search for a predictable formula ( 5 paragraph essay, anyone?), derived from a linear process (brainstorm - draft - revise - edit - publish). Or, teachers dictate what's important to students by always providing a prompt. I've come to the conclusion that the main reason teachers struggle to teach writing effectively stems from the fact that most teachers don't view themselves as writers. If we were to stop and consider the times in our lives when we are operating as authentic writers, I think we'd see that 1) there are lots and lots of formats within any given genre (and few, if any, of them are five paragraphs in length!), 2) we don't always follow a strict process - sometimes we gather ideas; sometimes we just write; and sometimes we make a plan first. Finally, 3) we decide what's important to write about, why we're writing, and whom we're writing for. In that vain, I've been gathering some resources to help you become a model writer for your classroom. Hopefully you'll find something useful! I challenge you to become the type of writer we want our students to be. Resources for Writing TeachersHere are some webpages and insights from some of my favorite writing teaches. One thing they have in common is that they're all writers themselves. Ralph FletcherThese tips are geared specifically toward student writers, but as writing teachers, we can use these tips as minilessons or conferring points. Ruth AyresThese images from Ruth Ayres's writing notebook provide a concrete example of what a writing notebook might look like. Don GravesIn this video interview, Don Graves discusses the writer's life. Useful stuff when trying to create a vision for a writing classroom.

I wanted a perfect ending. Now, I've learned, the hard way, that some poems don't rhyme, and some stories don't have a clear beginning, middle and end. Life is about not knowing, having to change, taking the moment and making the best of it, without knowing what's going to happen next. Delicious ambiguity.

- Gilda Radner I came across this quote from Gilda Radner on some random quote generator awhile back, and it stuck with me. I wasn't quite sure how it applied, but I knew that I'd figure it out eventually.

This year, our sixth grade reading teachers (Katie Anderson, Cele Fakler, Emily Glasford, Jannette Moehlman, Tara Knowlton, Hanne Burke, Lori Mettler, Lacey Bodensteiner, Pam Bonar, Anna Rau, and Monica Waltman) have committed to providing responsive, point-of-need teaching based on a series of assessments that will hopefully provide a more complete picture of our students as readers.

It hasn't been easy. There have been lots of new resources to learn about, and a little anxiety about how all of this would come together. And we're a long way from any type of perfect ending.

I wanted to use this forum as a way to publicly acknowledge the hard work and dedication of these outstanding educators. Even with the uncertainty of working with something new, these teachers have embraced the changes and taken the leap.

Thanks for all you do for our students!

I've been struggling to decide what to write as we dive head first into this new school year. Instead of coming up with something mediocre and uninspiring, I'd like to share a few words from one of my favorite educators, Cris Tovani: Rigor invites engagement. Hard repels it. When learners are engaged in something rigorous, they lose track of time. When the activity is hard, time seems to drag on endlessly. Learners who experience rigor, feel encouraged, self-confident, and have a sense of accomplishment. Hard is often trademarked by discouragement, avoidance, and a feeling that the effort spent doing the activity is a waste of time.

Our beliefs about rigor affect how we approach instruction. For me rigor isn’t tied to quantity or rate. It isn’t about the number of novels I blast through or the number of pages I assign for homework, or even how fast I cover content.

Rigor varies and depends on the learner’s skills and motivation to complete the task. It changes as the learner gains expertise. When it comes to rigor in the classroom, the bad news for teachers is that instead of having one high bar that all students are expected to reach, there needs to be several, adjustable bars that move as learners progress. Most importantly, rigor invites engagement because learners experience success. For me, if students aren’t engaged, I’m a very lonely teacher.

As you work with your teams to design Instructional Roadmaps and individual lesson plans, consider what it is you're asking of students. Is it rigorous, or merely hard? Source: http://www.literacylabs.org/

"What makes good poetry?"

This was a question that I asked my students last year after watching several youth poets perform their spoken word poetry. We also listened to contemporary music, and read a wide range of written poetry, and students were asked to reference the works that we've immersed our selves into. Here is my response:

In his spoken-word poem, "Urban Genocide," Berato Wilson says, "We die simply because nothing emphasizes life." Wilson was referencing the lower-class neighborhoods of Minneapolis and St. Paul, but his words struck me deeply. It is lines like these that drill down to the core of an issue in a way that only poetry can. By exposing the raw essence of a problem - the truth - we are forced to confront them. When poems are deeply personal and delivered with purpose and conviction, they transcend literature and become the anthems for our causes.

The Common Core State Standards don't emphasize poetry. Poetry is briefly mentioned in some of the reading standards; it is excluded entirely from the writing standards. But this doesn't mean that poetry should disappear from our curriculum. It does require more creativity on the part of teachers to figure out how to work poetry into an instructional plan in a meaningful way.

I urge you to consider how you can leverage the accessibility and personal nature of poetry in your classroom. Poetry can be used to reinforce reading standards (inferring and citing evidence immediately come to mind, as well as determining theme; in writing, poetry can help students with word choice, among other things).

If you have ideas or suggestions, please share them in the comments.

As we head into the Thanksgiving break, I'd like to propose that we take some time to think about what we're thankful for in our jobs.

Personally, I'm thankful to work with a great teaching staff, a strong administration that provides vision and support, and the secondary literacy team that gives me so much inspiration.

I would guess that many of us have similar lists that focus on our colleagues. But we have another group of people for whom we should be thankful:

Our students. Without students, our jobs wouldn't be necessary. And while it's required for students to come to school, it doesn't mean that it doesn't take some effort on their part to show up everyday. Being prepared and ready to learn merits some recognition.

Just like teachers, students put in long days. They get to school early, sit through seven hours of classes, and then go home to do homework.

Nick Provenzano (The Nerdy Teacher) reminds us that "these students in your class are people as well. They crave the same type of attention and reinforcement that all of us do."

Teaching can be thankless much of the time, but so can being a student. So this holiday season, try saying thank you to a student. If we want students to recognize the hard work we put into our lessons each day, we might try modeling this for students by thanking them for being in our classrooms.

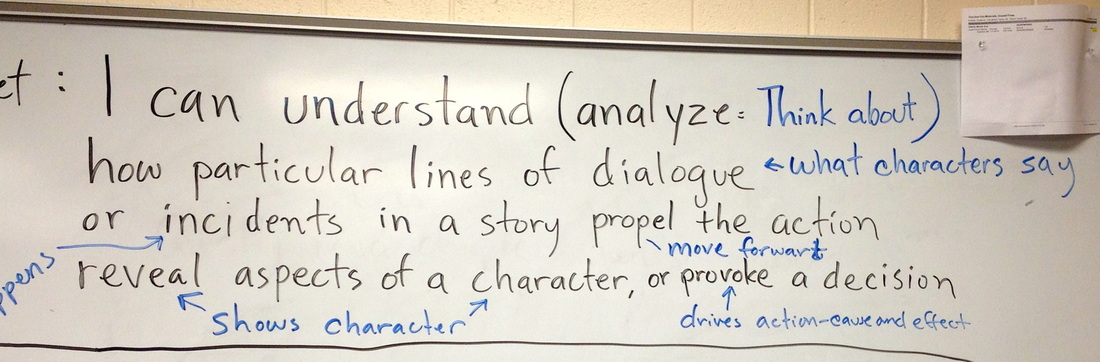

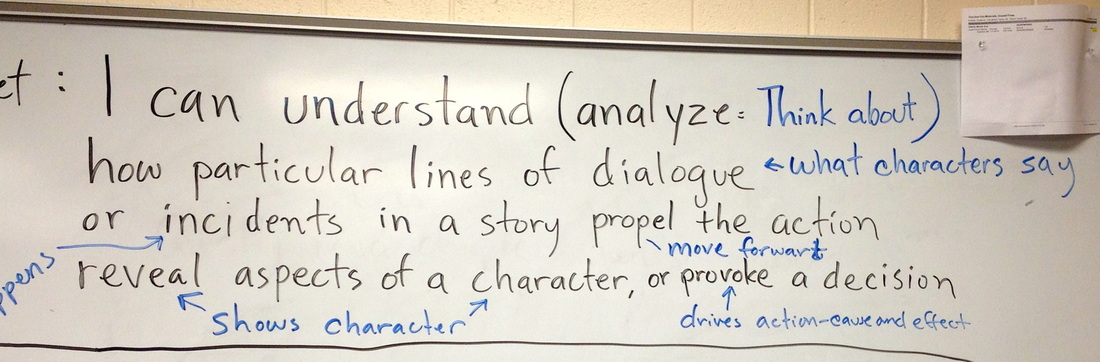

As we move further into our PLC work, we talk more and more about creating specific learning targets drawn directly from the standards. It is critical for our students that we generate good targets, and the accompanying criteria for success. So how do we know if we're doing it? Why Learning Targets?Before getting into the "how" of writing good targets and criteria for success, it may be helpful to think about why we should bother writing them in the first place. By providing students with a specific learning target, we reduce the anxiety many students feel when they walk into a classroom. To paraphrase Samantha Bennett (2007), think about all of the brain space that students can free up when they can focus on a target rather than trying to guess what the teacher has in store for them. Learning targets provide students with the purpose for being in your class on any given day. Robert Marzano (2001) has identified setting objectives (or learning targets) to be one of the most effective instructional strategies for improving student learning. Students are more likely to be able to tune out nonessential information, and retain more information that specifically relates to the target. Defining Learning Targets and Criteria for SuccessSo what is a learning target? How about criteria for success? How are they related? A learning target "says what a learner is expected to know or be able to do" at the end of instruction. (Marzano, 2001) These targets should be derived from the standards by disaggregating the standards first. I outlined a process for unwrapping standards, adapted from Chris Jakicic and Larry Ainsworth, here. These targets should be written in student friendly language, using "I can..." or "I know..." as much as possible. Criteria for success outline the conditions and criterion for meeting the learning target. The criteria for success will tell students in what format you expect them to respond (i.e., "in writing" or "orally") and what level of response is required (i.e., "in at least three paragraphs" or "citing two specific examples of textual evidence"). Often, but not always, the criteria for success describes the product or result. Here's an example:Learning target: I can write a conclusion for my op-ed piece. Criteria for success: In your writing notebook draft a conclusion for your op-ed, using one of the following strategies: - admonition

- prediction

- pointed question

In this example, the learning target tells them what they're learning to do (write a conclusion); the criteria for success outlines the conditions (in the writing notebook) and the criterion (draft one of three styles of conclusions). Communicating Targets EffectivelyJust as important as designing a good learning target is being able to communicate the target to students in a way that they'll understand and be able to reference. Learning targets and criteria for success should be posted for students to reference. But we can't stop there. If you're using student friendly language, you've got a good start. Often, standards (and consequently, learning targets) are still written using language that is foreign to students. When this is the case, we have to walk them through the target. By doing this, we're minimizing misconceptions and teaching academic vocabulary. In Richard Jones's 8th grade ELA classroom, you can see a great example of a learning target being deconstructed for students:

The original learning target is in black; the breakdown for students is in blue. Because of the way the learning target was communicated, Mr. Jones's students are more likely to understand what their purpose is in class, and they're more likely to hit the mark. As you move forward in your instructional planning, consider how you can write and communicate your learning targets and criteria for success to your students. Resources:- Bennett, Samantha. (2007) That Workshop Book. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Marzano, R. J., Pickering, D. J., & Pollock, J.E. (2001). Classroom Instruction That Works. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

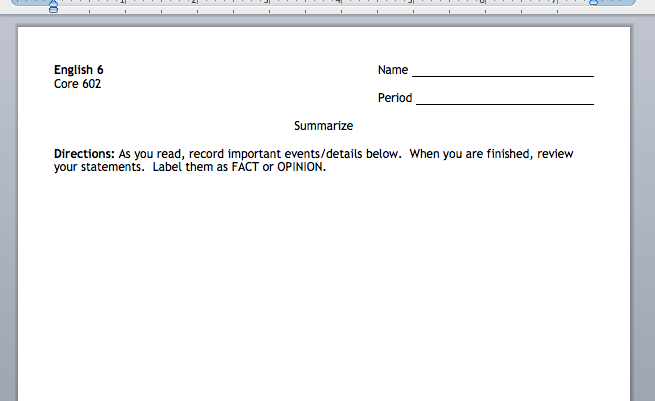

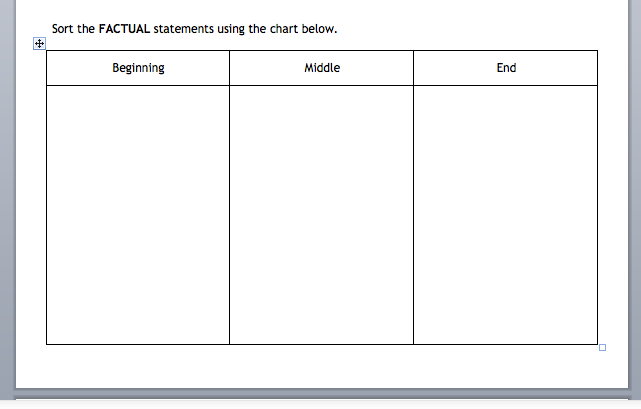

The PLC process can be complicated, time consuming, and frustrating. In particular, the work of creating a common formative assessment (CFA) can feel particularly cumbersome; as another educator pointed out to me recently, any one of us could probably create a serviceable assessment on our own in far less time. But, the product of our collaborative efforts often exceed what we can do on our own. The 6th Grade ELA/Reading team of Hanne Burke, Amanda Hepburn, and Lori Mettler came up with an outstanding example of a CFA for summarizing (the document can be downloaded below). Here are some things I like about this particular assessment: - It's universal. The assessment isn't tied to any one text in particular; a teacher could use this with students' self-selected texts. It can be used as a summative assessment with a common text. And, obviously, it can be used as a CFA.

- It's flexible. Take a look at the image below. Students can record their findings directly on the page, or they could use sticky notes and stick them to the assessment. There's room for a student to draw a graphic organizer of their own design. This allows for teachers (and students) to use their own approaches and styles, without compromising the integrity of the assessment.

- It's scaffolded. The design of the assessment, including the graphic organizer below, allows teachers to see exactly where student understanding breaks down. By setting up the assessment this way, the team gets more discrete data and they can then create a more appropriate response.

- It's appropriately rigorous. While the assessment is scaffolded, the final task (below) asks students to create a product that is at the level of cognitive demand required by the standard.

Implications for Practice:As you go about creating your own assessments, consider:- the language of your standard. Does the assessment reflect that language? For example, this assessment is designed for 6.RL.2; 8.RL.2 mentions specific literary elements (character, setting, plot). How would you adapt this assessment to meet the demands of the 8th grade standard?

- the usability of the assessment. Can you use the assessment without teaching a specific text? If not, you might want to make some modifications. This isn't to say that you could never have a text-dependent assessment; but you might consider basing your assessment on a more general template.

- what skills you need to teach students in order to take the assessment. If students have never used a graphic organizer like the one in the assessment, you might consider modeling it for the students first.

Finally, consider the overall intent of the standard. Do we just want kids to summarize for the sake of summarizing? If that were the case, we'd create a two-week summarizing unit, assess our kids and move on. Or do we want kids to write a summary as a gateway to deeper analysis? Something to mull over.

Standard W.4 (grades 6-8) ask students to: Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.Wow. Thats pretty loaded, huh? As I went through the unwrapping process with one of my teachers recently, we pulled out nine explicit targets - and that was before we thought about all of the targets involved with Standards W.1, 2, and 3! Before diving into the standard as a whole, it helps to focus on just a few aspects of the standard. I'm starting with two: Audience and purpose. Carl Anderson (2005) says that lifelong writers initiate writing. What does it mean to be an initiator of writing? According to Anderson, two of the characteristics of initiators of writing are: - writing for various purposes

- writing for real audiences

Summarizing requires students to distill information Earlier this month, I wrote about Standard RL.2 and theme; the standard actually has two parts. The first part deals with theme, and the second asks students to summarize. This is a case where the standards and effective teaching strategies overlap. The standard requires us to teach students to summarize; the act of summarizing helps students to achieve at higher levels. According to Robert Marzano (2001), summarizing is one of the most effective instructional strategies we have at our disposal, with an average effect size of 1.00 (in other words, a 34-point percentile gain). Based on his meta analysis of the research on summarizing, Marzano extracts three generalizations: - To effectively summarize, students must delete some information, substitute some information, and keep some information.

- To effectively delete, substitute, and keep information, students must analyze the information at a fairly deep level.

- Being aware of the explicit structure of information is an aid to summarizing information.

When we want students to summarize, we can help them by providing specific summarizing strategies. Two strategies that can be used to help meet the requirements of Standard RL.2 are rule-based summarizing, and summary frames. Rule-Based SummarizingRule-based summarizing comes from generalizations 1 and 2. This strategy involves a set of rules or steps that students use to construct a summary: - Take out material that is not important for your understanding.

- Take out words or passages that repeat information.

- Replace a list of things with a word that describes the things in the list (e.g. use "trees" for "elm, oak, and maple").

- Find a topic sentence or invent one if it is missing

adapted from Brown, Campione, & Day (1981)The document below is an example of rule-based summarizing in practice.

Summary FramesSummary frames are a direct application of generalization 3. A summary frame is a series of questions provided for students designed to highlight specific elements for different types of information. Each frame captures the basic structure of a different type of text. Below, you will find six types of summary frames: - The Narrative Frame

- The Topic-Restriction-Illustration Frame

- The Definition Frame

- The Argumentation Frame

- The Problem/Solution Frame

- The Conversation Frame

adapted from Marzano (2001)Using these rule-based summarizing or summary frames can be an effective scaffold for students. As students become more familiar with summarizing, you can begin to remove these supports. For additional resources, check here. Resources:

- Marzano, R. J., Pickering, D. J., & Pollock, J.E. (2001). Classroom Instruction That Works. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Marzano, R. J., Norford, J. S., Paynter, D. E., Pickering, D. J., & Gaddy, B. B. (2001). A Handbook for Classroom Instruction That Works. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Jake was one of my favorite books as a kid. My mom was a middle school librarian, and I never wanted for great books to read. I remember when she brought Jake home for me, I was so excited. It was about a kid my age, and the setting was my home town. And, it was about baseball!. I didn't know it at the time, but my mom was a master at doing book talks, and matching readers (in this case, me) to texts. I hadn't thought about this book in probably close to 20 years. So I was thrilled to find an article about the book on Grantland.com. The article features Bill Simmons reaction to a short film about the book, and the first two chapters of the book, which has been out of print since 1981. Reading those chapters transported me back to a time when I was learning to love to read. I was lucky to have parents who encouraged and celebrated reading. The article contains a link to a short film by Jonathan Hock, in which he interviews the author, Alfred Slote, now 86 years old. If you're looking for an example of an author talking about his writing process, this is pretty great. You also get a true sense of how meaningful the work was for him. These are two things we should be talking to students about: developing a writing process that works for them, and writing about something truly meaningful.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed