As we head into the Thanksgiving break, I'd like to propose that we take some time to think about what we're thankful for in our jobs.

Personally, I'm thankful to work with a great teaching staff, a strong administration that provides vision and support, and the secondary literacy team that gives me so much inspiration.

I would guess that many of us have similar lists that focus on our colleagues. But we have another group of people for whom we should be thankful:

Our students. Without students, our jobs wouldn't be necessary. And while it's required for students to come to school, it doesn't mean that it doesn't take some effort on their part to show up everyday. Being prepared and ready to learn merits some recognition.

Just like teachers, students put in long days. They get to school early, sit through seven hours of classes, and then go home to do homework.

Nick Provenzano (The Nerdy Teacher) reminds us that "these students in your class are people as well. They crave the same type of attention and reinforcement that all of us do."

Teaching can be thankless much of the time, but so can being a student. So this holiday season, try saying thank you to a student. If we want students to recognize the hard work we put into our lessons each day, we might try modeling this for students by thanking them for being in our classrooms.

As we move further into our PLC work, we talk more and more about creating specific learning targets drawn directly from the standards. It is critical for our students that we generate good targets, and the accompanying criteria for success. So how do we know if we're doing it? Why Learning Targets?Before getting into the "how" of writing good targets and criteria for success, it may be helpful to think about why we should bother writing them in the first place. By providing students with a specific learning target, we reduce the anxiety many students feel when they walk into a classroom. To paraphrase Samantha Bennett (2007), think about all of the brain space that students can free up when they can focus on a target rather than trying to guess what the teacher has in store for them. Learning targets provide students with the purpose for being in your class on any given day. Robert Marzano (2001) has identified setting objectives (or learning targets) to be one of the most effective instructional strategies for improving student learning. Students are more likely to be able to tune out nonessential information, and retain more information that specifically relates to the target. Defining Learning Targets and Criteria for SuccessSo what is a learning target? How about criteria for success? How are they related? A learning target "says what a learner is expected to know or be able to do" at the end of instruction. (Marzano, 2001) These targets should be derived from the standards by disaggregating the standards first. I outlined a process for unwrapping standards, adapted from Chris Jakicic and Larry Ainsworth, here. These targets should be written in student friendly language, using "I can..." or "I know..." as much as possible. Criteria for success outline the conditions and criterion for meeting the learning target. The criteria for success will tell students in what format you expect them to respond (i.e., "in writing" or "orally") and what level of response is required (i.e., "in at least three paragraphs" or "citing two specific examples of textual evidence"). Often, but not always, the criteria for success describes the product or result. Here's an example:Learning target: I can write a conclusion for my op-ed piece. Criteria for success: In your writing notebook draft a conclusion for your op-ed, using one of the following strategies: - admonition

- prediction

- pointed question

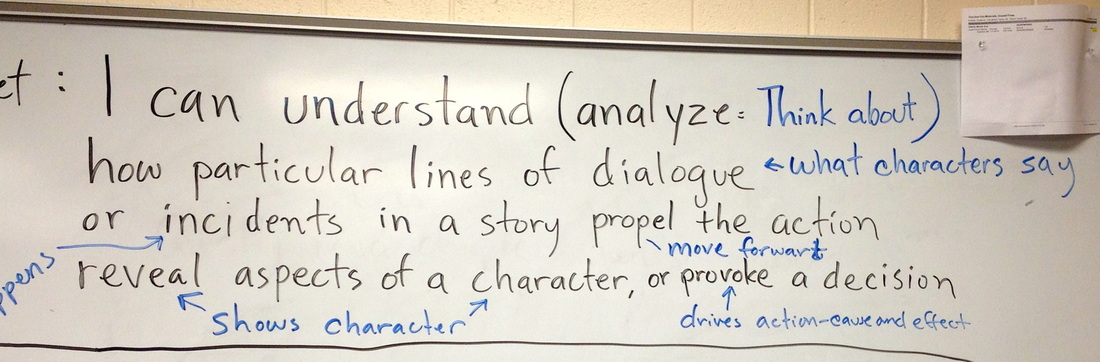

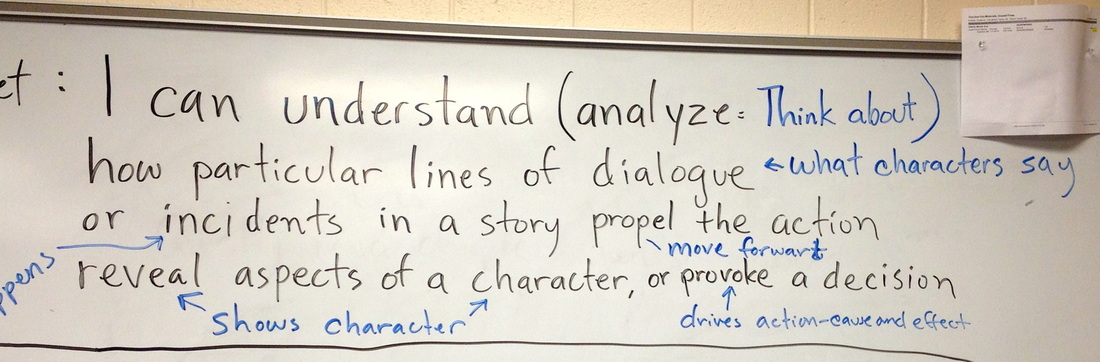

In this example, the learning target tells them what they're learning to do (write a conclusion); the criteria for success outlines the conditions (in the writing notebook) and the criterion (draft one of three styles of conclusions). Communicating Targets EffectivelyJust as important as designing a good learning target is being able to communicate the target to students in a way that they'll understand and be able to reference. Learning targets and criteria for success should be posted for students to reference. But we can't stop there. If you're using student friendly language, you've got a good start. Often, standards (and consequently, learning targets) are still written using language that is foreign to students. When this is the case, we have to walk them through the target. By doing this, we're minimizing misconceptions and teaching academic vocabulary. In Richard Jones's 8th grade ELA classroom, you can see a great example of a learning target being deconstructed for students:

The original learning target is in black; the breakdown for students is in blue. Because of the way the learning target was communicated, Mr. Jones's students are more likely to understand what their purpose is in class, and they're more likely to hit the mark. As you move forward in your instructional planning, consider how you can write and communicate your learning targets and criteria for success to your students. Resources:- Bennett, Samantha. (2007) That Workshop Book. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Marzano, R. J., Pickering, D. J., & Pollock, J.E. (2001). Classroom Instruction That Works. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

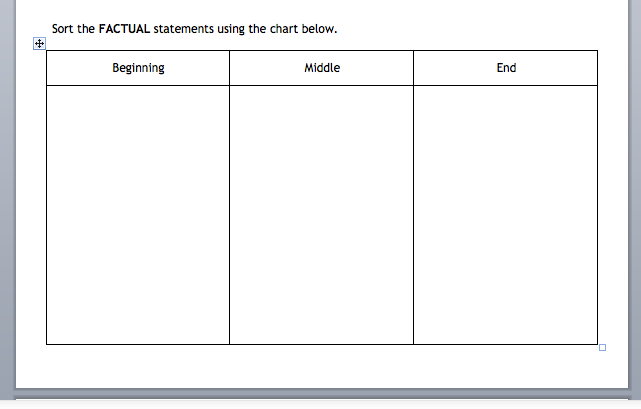

The PLC process can be complicated, time consuming, and frustrating. In particular, the work of creating a common formative assessment (CFA) can feel particularly cumbersome; as another educator pointed out to me recently, any one of us could probably create a serviceable assessment on our own in far less time. But, the product of our collaborative efforts often exceed what we can do on our own. The 6th Grade ELA/Reading team of Hanne Burke, Amanda Hepburn, and Lori Mettler came up with an outstanding example of a CFA for summarizing (the document can be downloaded below). Here are some things I like about this particular assessment: - It's universal. The assessment isn't tied to any one text in particular; a teacher could use this with students' self-selected texts. It can be used as a summative assessment with a common text. And, obviously, it can be used as a CFA.

- It's flexible. Take a look at the image below. Students can record their findings directly on the page, or they could use sticky notes and stick them to the assessment. There's room for a student to draw a graphic organizer of their own design. This allows for teachers (and students) to use their own approaches and styles, without compromising the integrity of the assessment.

- It's scaffolded. The design of the assessment, including the graphic organizer below, allows teachers to see exactly where student understanding breaks down. By setting up the assessment this way, the team gets more discrete data and they can then create a more appropriate response.

- It's appropriately rigorous. While the assessment is scaffolded, the final task (below) asks students to create a product that is at the level of cognitive demand required by the standard.

Implications for Practice:As you go about creating your own assessments, consider:- the language of your standard. Does the assessment reflect that language? For example, this assessment is designed for 6.RL.2; 8.RL.2 mentions specific literary elements (character, setting, plot). How would you adapt this assessment to meet the demands of the 8th grade standard?

- the usability of the assessment. Can you use the assessment without teaching a specific text? If not, you might want to make some modifications. This isn't to say that you could never have a text-dependent assessment; but you might consider basing your assessment on a more general template.

- what skills you need to teach students in order to take the assessment. If students have never used a graphic organizer like the one in the assessment, you might consider modeling it for the students first.

Finally, consider the overall intent of the standard. Do we just want kids to summarize for the sake of summarizing? If that were the case, we'd create a two-week summarizing unit, assess our kids and move on. Or do we want kids to write a summary as a gateway to deeper analysis? Something to mull over.

Standard W.4 (grades 6-8) ask students to: Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.Wow. Thats pretty loaded, huh? As I went through the unwrapping process with one of my teachers recently, we pulled out nine explicit targets - and that was before we thought about all of the targets involved with Standards W.1, 2, and 3! Before diving into the standard as a whole, it helps to focus on just a few aspects of the standard. I'm starting with two: Audience and purpose. Carl Anderson (2005) says that lifelong writers initiate writing. What does it mean to be an initiator of writing? According to Anderson, two of the characteristics of initiators of writing are: - writing for various purposes

- writing for real audiences

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed