Summarizing requires students to distill information Earlier this month, I wrote about Standard RL.2 and theme; the standard actually has two parts. The first part deals with theme, and the second asks students to summarize. This is a case where the standards and effective teaching strategies overlap. The standard requires us to teach students to summarize; the act of summarizing helps students to achieve at higher levels. According to Robert Marzano (2001), summarizing is one of the most effective instructional strategies we have at our disposal, with an average effect size of 1.00 (in other words, a 34-point percentile gain). Based on his meta analysis of the research on summarizing, Marzano extracts three generalizations: - To effectively summarize, students must delete some information, substitute some information, and keep some information.

- To effectively delete, substitute, and keep information, students must analyze the information at a fairly deep level.

- Being aware of the explicit structure of information is an aid to summarizing information.

When we want students to summarize, we can help them by providing specific summarizing strategies. Two strategies that can be used to help meet the requirements of Standard RL.2 are rule-based summarizing, and summary frames. Rule-Based SummarizingRule-based summarizing comes from generalizations 1 and 2. This strategy involves a set of rules or steps that students use to construct a summary: - Take out material that is not important for your understanding.

- Take out words or passages that repeat information.

- Replace a list of things with a word that describes the things in the list (e.g. use "trees" for "elm, oak, and maple").

- Find a topic sentence or invent one if it is missing

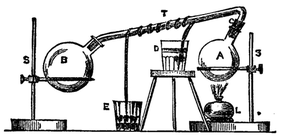

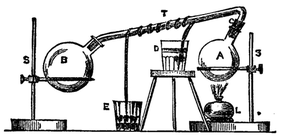

adapted from Brown, Campione, & Day (1981)The document below is an example of rule-based summarizing in practice.

Summary FramesSummary frames are a direct application of generalization 3. A summary frame is a series of questions provided for students designed to highlight specific elements for different types of information. Each frame captures the basic structure of a different type of text. Below, you will find six types of summary frames: - The Narrative Frame

- The Topic-Restriction-Illustration Frame

- The Definition Frame

- The Argumentation Frame

- The Problem/Solution Frame

- The Conversation Frame

adapted from Marzano (2001)Using these rule-based summarizing or summary frames can be an effective scaffold for students. As students become more familiar with summarizing, you can begin to remove these supports. For additional resources, check here. Resources:

- Marzano, R. J., Pickering, D. J., & Pollock, J.E. (2001). Classroom Instruction That Works. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Marzano, R. J., Norford, J. S., Paynter, D. E., Pickering, D. J., & Gaddy, B. B. (2001). A Handbook for Classroom Instruction That Works. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Jake was one of my favorite books as a kid. My mom was a middle school librarian, and I never wanted for great books to read. I remember when she brought Jake home for me, I was so excited. It was about a kid my age, and the setting was my home town. And, it was about baseball!. I didn't know it at the time, but my mom was a master at doing book talks, and matching readers (in this case, me) to texts. I hadn't thought about this book in probably close to 20 years. So I was thrilled to find an article about the book on Grantland.com. The article features Bill Simmons reaction to a short film about the book, and the first two chapters of the book, which has been out of print since 1981. Reading those chapters transported me back to a time when I was learning to love to read. I was lucky to have parents who encouraged and celebrated reading. The article contains a link to a short film by Jonathan Hock, in which he interviews the author, Alfred Slote, now 86 years old. If you're looking for an example of an author talking about his writing process, this is pretty great. You also get a true sense of how meaningful the work was for him. These are two things we should be talking to students about: developing a writing process that works for them, and writing about something truly meaningful.

As November approaches, our attention should be shifting to the next set of Power Standards. Last week, I wrote a post related to RL.2. This week, I'll be focusing on W.4. My personal experience as a writer - from middle school, high school, and even college to some extent - was highly standardized; as a result, I came to teaching with a lens for looking at student writing that was heavy on conventions: grammar, punctuation, spelling. For several years, "teaching" writing involved posting a prompt, and then returning responses with lots of red marks on them - circled incorrect spelling and punctuation, and brief comments: "vague" or "expand". I was serving as an editor rather than a teacher, and unfortunately this didn't provide my students with much direction, other than to try to get less red ink on the next paper. Two years ago, I had the opportunity to spend a few days working with Carl Anderson, author of How's It Going? and Assessing Writers. I left the workshop with three "ah ha's": - Conventions are only one piece of the puzzle; I needed to be a reader of student writing, not an editor

- To teach writing, I had to be a writer myself; my students needed to know that I was struggling alongside them [Update: check out this link for another perspective on this point]

- I needed to develop an assessment lens for looking at student writers that focused on what I wanted my students to become, and how the act of writing could help them to become the best version of themselves

As a result of my work with Mr. Anderson, I developed a vision for my students that focused on audience, purpose, meaning, and genre knowledge. I still taught detail, structure, voice, and conventions, but they were viewed with the intent of the student's writing in mind, and always built on what the student could already do well. I always had my own writing notebook and a few mentor texts handy to share with students while conferring with them. Standard W.4 focuses on development, organization, and style in relation to task, purpose and audience. This doesn't mean you have to completely ignore grammar, syntax, and spelling; it does mean that when you emphasize those things, you aren't addressing this standard. Keep that in mind as you create your common formative assessments. As you work with student writers, remember that they will often accomplish incredible things while crafting their writing; our job is to find it, name it, and encourage it. Learn to notice the beauty in student writing that is often hidden behind conventional errors, and get excited by what your students know and can do. Kathryn Bomer (2010) eloquently states this sentiment in her book, Hidden Gems: Naming and Teaching from the Brilliance in Every Student's Writing, when she says, "when I'm able to read past all those surface problems, what I find in young people's writing is passionate, surprising, and endearing enough to convince me that I have the best job on the earth."

The RCAS Curriculum Guide outlines two power standards for November/December: - RL.2: Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas.

- W.4: Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

As you plan upcoming units, you may find yourself asking this question relating to RL.2: What, exactly, is this thing called theme, and how am I going to communicate it to students? First, let's talk about what theme isn't. Theme is not the same as topic. Friendship, love, growing up, death; these are topics. As Johnston and Afflerbach (1985) put it, identifying the topic of a text is "only the halfway point." Now, what is theme? Theme is where all the other literary elements come together to fulfill a text's ultimate purpose. In their book, Fresh Takes on Teaching Literary Elements: How to Teach What Really Matters About Character, Setting, Point of View, and Theme, Michael W. Smith and Jeffrey D. Wilhelm (2010) say, "When we see characters play out various values and perspectives in particular circumstances, when we see situations, perspectives, and values change, we see themes come to life." A theme is more specific than a topic; a theme contains both the topic and a comment. The theme of a fable is its moral. The theme of a parable is its teaching. A novel's theme is a statement that the author makes about life. Edward B. Fry (2006) states that theme is, "the message about life or nature that the author wants the reader to get from the story, play, or poem." Theme reflects the human condition. Although the details of a reader's experiences may be different from the details of the story, the underlying message of the story may be the connection that both the reader and the writer are seeking. In general, the theme of a narrative can be written as a statement: Friendship can be lost if you don't nurture it; It is better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all; Death comes for us all. Theme is usually not presented directly. You extract it from the characters, action, and setting that make up the story. In other words, you must figure out the theme yourself. So how do we help kids determine the theme of a narrative? Try having students answer these questions to help guide them in finding the theme: - What topics or big ideas is the story about?

- What do characters say or do that relates to that topic?

- What do these things tell you is important to learn about life?

Remember that the standard asks for considerably more than simply identifying the theme - but it is a place to start.

Over the past few weeks, I've heard from teachers who are concerned about the reading levels of some of their students. Using data from CBMs and the GMRT, staff members have identified students who are really struggling, and are wondering what they can do to help those students succeed. According to a meta-analysis done by Guthrie and Humenick (2004), there are a few classroom factors that are most strongly related to success in reading: - Access to high-interest texts

- Choice in reading material

- Time to read

The most influential factor is provisioning students with an extensive collection of high-interest books. Lucy Calkins says the minimum number of books in a good classroom library is about 20 books per student per reading block; over time, it will be important to provide even more than that (2012). High-performing classrooms are filled with books of different levels of difficulty. (Pressley, 2003) Here at East Middle School, Lori Mettler has set up a classroom library that is filled with high interest titles - and she's always adding more. Stop in and check it out if you have a few minutes. Choice in reading material is the second most influential factor related to success in reading. Having an extensive library is a first step, but it isn't enough. Helping kids to choose books at or slightly above their current level is necessary as well. The lack of choice can undermine motivation and achievement. (Pressley et al., 2003; Guthrie, 2004) Finally, students have to have time to read every day. In Guthrie's (2004) findings, "reading volume predicted reading comprehension." Education researcher Richard Allington (2002) confirms these findings: students in the classrooms of the most effective teachers read ten times as much as students in classrooms of less effective teachers. As Calkins states, "The engine that motors readers' development is the time spent engaged in reading and in talking and writing about that reading." So, what can you do with the resources you have? First, reflect on your current practices and classroom environment. Do kids have access to books? If not, how often can you get to the library? Ask Corinne Miller for a copy of Fountas and Pinnell's Leveled Book List so that you can help match kids to texts. You could also create a Donor's Choose project to add books (and other supplies) to your classroom library at no cost to you or the school district. BetterWorldBooks.com is another source for inexpensive books to add to your library - and every book purchase you make, they'll donate a book to a high need community. What about your current classroom structure? The workshop model allows for students to choose texts to read, and the structure and routine of workshop provide plenty of time to read everyday. Our very own South Dakota Teacher of the Year, Katie Anderson, runs an outstanding reading workshop during her 6th grade reading class if you're looking for an example of workshop in action. Resources:Allington, Richard. 2002. "You Can't Learn Much from Books You Can't Read." What Really Matters for Struggling Readers: Designing Research Based Programs. 2d ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Calkins, Lucy, Mary Ehrenworth, and Christopher Lehman. 2012. Pathways to the Common Core: Accelarting Achievement. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Guthrie, John T., and Nicole Humenick M. 2004. "Motivating Students to Read: Evidence for Classroom Practices That Increase Reading Motivation and Achievement." In The Voice of Evidence in Reading Research, edited by Peggy McCardle and Vinita Chhabra, 329-54. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing

Pressley, Michael, Sara E. Dolezal Kersey, Lisa Raphael Bogaert, Lindsey Mohan, Alysia D. Roehrig, and Kristen Warzon. 2003. Motivating Primary-Grade Students. New York: Guilford Press.

The long awaited Gates-MacGinnitie testing window is open, and today we started assessing our first batch of students. Outside of a few minor technical glitches, things went relatively smoothly. A special thank you to Mrs. Hepburn and Mrs. Burke for being the guinea pigs for East, and to Mrs. Goebel for letting us use her classroom for overflow. Also, for all of the non-English teachers, I appreciate your flexibility while I arranged the scheduling. I know it can be frustrating to have to change plans on short notice, but everyone was extremely accommodating and understanding. A couple of notes about GMRT proctoring: - Remember to finalize your session after the comprehension test.

- Please email me a list of students who didn't finish all of their testing.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed